Company history.

It all started in 1876, 800 feet up on a Pennine hillside

Back in the 1800s long before recycling became a buzz word the Schofield family were hard at work earning a living recycling any suitable material that came their way, typically woollen waste, leather belting and wooden bobbins, anything that the area's booming textile industry could reuse.

James Schofield, born in 1828, and his wife Elizabeth bought land and property on the present site at Greenhead, Linthwaite, 800ft up on a Pennine hillside in 1876. The deeds for the land show him to have been a woollen waste dealer. James died in 1892 with the property passing to his wife. Upon her death in 1908 Joe Benjamin (J.B.) Schofield, one of James's 4 children, paid £700 for the property and 3 acres of land and the business of J.B. Schofield was born, by now dealing in scrap metal. Originally the earliest paperwork that the company could find referred to 1912, this refers to J B Schofield specifically however with James having been in business at least 40 years before this date.

A challenging location in winter rain, wind and snow, the rain usually horizontal and travelling at 60mph.

J.B. Schofield (Joe) had 4 sons 2 of whom, Norman and Stanley took the opportunity in 1920 to buy for the princely sum of £410 another 8 acres of land to add to what was already in the family. Later in 1941 Norman paid £800 to buy the rest of the family’s share in all the land and property at Greenhead thus setting the scene for the next 3 generations of Schofields.

Like most other business of the time the horse and cart was the transport of the day. However in 1933, 13 years after Joe's death, the first diesel engine vehicles came along, YG8732, a Morris commercial. By 1954, following the lean post war years Norman, encouraged by sons Carl and George, had scraped the money together to buy the company’s first new vehicle, a Perkins P6 engined Dodge 5 tonner based on payload in those days of course. Norman told the two that this would be the last new wagon he would ever buy. He did, however buy the business of W. Oldcorn from his friend William Bill Oldcorn, involved in coal and general haulage W. Oldcorn still trades from the same office as J.B. Schofield.

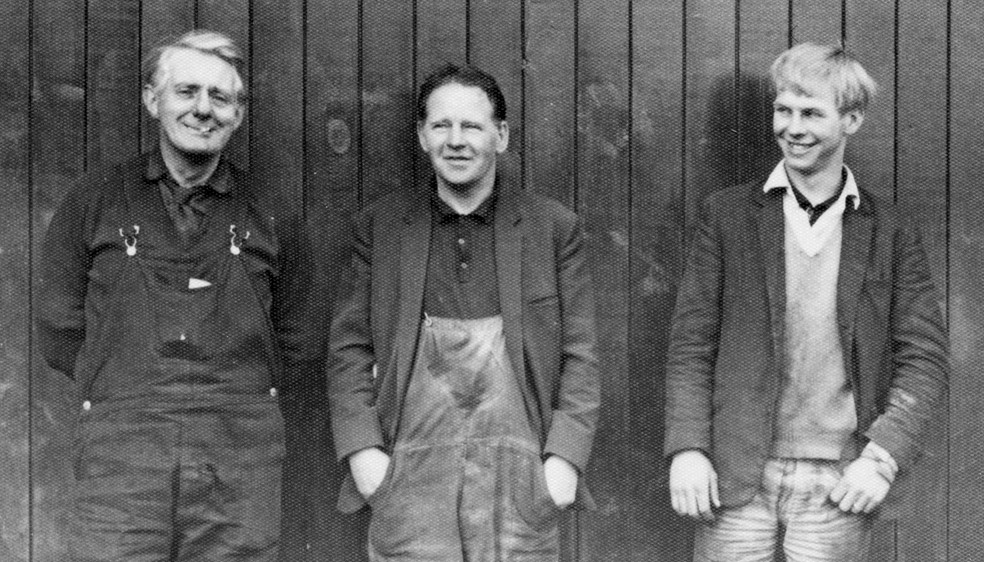

Norman’s death at the age of 67 in 1964 led to Carl and younger brother George taking over the business with some stock but very little money. The two brothers set about expanding the company forming J.B. Schofield & Sons Ltd. Larger vehicles, Foden, probably the best premium vehicle of that era were the chosen marque, forming a trend that is carried to the current day. A new crane with electro magnet for handling the ferrous scrap metal, crawler excavators, wheeled loaders and crawler cranes were all acquired with demolition and plant hire being undertaken.

Most other merchants were breaking in filthy conditions.

Schofield's refined breaking process with drainage meant that their cast iron was clean even in the depths of winter.

During the 1960s in Schofield’s home valley the Colne Valley, famous for its textile mills, rows of stone weavers cottages built to service the now declining industry were being condemned and demolished and replaced with modern housing thus keeping the demolition equipment busy. Larger industrial demolition sites were of course providing scrap metal for the scrap processing side of the business. Many of the new houses were being built from the same stone and wood reclaimed from the destruction of the houses being replaced, many houses in the Huddersfield area being built from materials supplied by Schofield’s.

Although textiles were declining the local villages were growing providing yet more work for the plant hire business, stripping soil and sub soil in conjunction with local developers. These one-time fields are now unrecognisable as such - they have been turned into sprawling housing estates.

Back in the scrapyard at Greenhead, redundant machinery from the textile industry was being processed into high quality feedstock for local foundries and Sheffield’s steelworks.

Even further afield, Skinningrove’s famous steelworks in the northeast was a regular destination by both day and night for Schofield’s larger vehicles, a 216 mile round trip, the journey was a long day's work for stalwart driver Harold Brown, a character and long-time employee who was familiar with most of the pub landlords en-route from Greenhead to Skinningrove! Another regular customer was the Dick Lane foundry of English Electric in Bradford. Carl struck up a friendship with Harry Wilkinson, the purchasing manager. English Electric was to become the bedrock of Schofield’s ferrous scrap metal business during the 70s and 80s. The cupolas at Dick Lane foundry needed up to 800 tonnes a month of low phosphorous cast iron broken no larger than 18′ plus sheared short steel; this low phosphorous or grade 17 cast iron was to be Schofield’s speciality. Material was both delivered and collected by Schofield’s from merchants all over the UK, at the same time Carl was persuading Harry to accept grade 17 cast iron skull broken small and blended with the other broken castings, brake drums and engines.

Skull could be bought cheaper therefore raising the margin on the whole load. On top of this the breaking process was refined, a purpose made breaking pit with 12′ thick steel plates on top of each other bedded in up to 3′ of tarmac, with drainage meant that even in the depths of winter Schofield’s cast iron was clean. Most other merchants were breaking in filthy conditions.

Schofield's remote rural hilltop location meant that scrap had to sourced from far and wide, therefore modern, reliable transport had to be the order of the day.

A larger 1.25 tonne steel breaking ball, a crane with a 40ft jib instead of 30′ meant that cast up to 12′ thick could be broken, this in turn meant that they could break material the others wouldn’t or couldn’t touch. All incoming materials were analysed, checking for correct carbon, silicon and phosphorous levels, in fact up to 16 trace elements were checked. This extra information meant that Schofield’s could more accurately blend the cast iron mix. As well as being sole suppliers to the site by now there were separating and screening plants permanently based on the foundry tip, fed by Schofield’s dragline and loading shovels separating the metals running from the black foundry sand, a waste skip service taking waste to nearby landfill sites. Sadly all this was to end, with the sudden closure, for environmental reasons, of the foundry in 1990.

The next generation of Schofield’s had started their working lives in the business during the ’70s the first being Carl's eldest son Mark, brother George's sons Andrew, Richard and Michael all following later. This generation was having a very varied working life. From swinging the hammer breaking textile machinery in the mills and processing scrap in the yard, there now came local authority work.

Carl had had a chance meeting with the area engineer for the newly formed West Yorkshire Metropolitan Council, one Keith Dwyer, another of life’s great characters, Carl was invited to tender for hire work including winter road maintenance, gritting in other words, or better still snow ploughing, playing in the snow in large wagons and paid for the pleasure! What could be better? It became Carl’s passion, a sort of paid hobby, a change from breaking cast iron.

By 1980 almost every piece of equipment they owned that could be adapted to move snow had been: 16 bulk gritters, tippers with ploughs, crawler shovels, JCBs, everything and everybody was utilised in the big snows of the time, working 4.30am until midnight and even all night to keep the trans Pennine passes open.

A lot of the gritters that Schofield’s used were unique, built and modified in their own workshops, sandblasted and sprayed by Mark with the most effective rust preventative paint that money could buy.

The vehicles were never less than smart even though far from new. New vehicles couldn’t be justified on council rates of pay; most of the time it made a profit and most of the time, most of the workforce enjoyed doing it. There were occasions however when with his diesel frozen and waxed, salt frozen solid (yes it does freeze) and with hands and feet colder still, a driver might long to be home in his nice warm bed.

For Carl, one of the problems with gritting was that his precious stock piles of cast iron, pre-broken ready for delivery should unforeseen circumstances prevent him breaking, would dwindle whilst he was out in his snowplough playing in the snow. To counter this as soon as the weather permitted he would break with a vengeance , so year on year the piles grew bigger and the roadways around the site narrower. By the time Dick lane foundry closed there was enough stock for around two years of melting left.

Schofield’s remote rural hill top location means that scrap has to be sourced from far and wide therefore modern reliable transport has to be the order of the day. Schofield’s smartly kept highly specified Fodens were a familiar sight on the northern roads for over 40 years. These vehicles along with the gritters have been featured in several Heritage Commercial magazine articles with words and photographs supplied by keen amateur photographer Marks archive of over 60,000 photographs.

The Greenhead site has seen much modernisation over the years: a non ferrous metal sorting shop, 4 bay vehicle workshop, tarmac roadways (since the early 70s), new weighbridge, site concrete, drainage, the introduction of strict Health & Safety rules and environmental legislation, IT systems, each in its turn affecting the working lives of the Schofield family, which by now sees Mark’s two sons, another Carl, and John, and latterly, his two daughters Leigh and Liz (J.B.) establishing their selves in the business, three generations all working together recycling, as they have for the last 130 years at Greenhead.

Greenhead has now been home as well as work to six generations of the Schofield family, any plans to expand into nearby towns scuppered because no one has ever wanted to work anywhere else.

To the outsider looking in Schofield’s legendary mountains of scrap seem to never change, in reality though much of the incoming material is processed and loaded for export the same day, only the higher grade foundry material being stockpiled until orders are received. The markets for recycled scrap metal have changed dramatically during the last 10 years, traditionally their scrap sales would be split 80-90% home consumption with the rest going to export, now the opposite is true. Schofield’s do however still supply most of the areas foundries, the large stocks ensuring that material is available no matter how large the order.

As for the future, probably more of the same, changes in legislation are challenges that have to be met, the lofty rural location, a pleasant place to work in summer, a challenging environment in winter rain, wind and snow. The rain usually being horizontal and travelling at 60mph. Challenging or not Greenhead has been home as well as work to six generations of the Schofield family, any plans to expand into nearby towns scuppered because none of them want to work anywhere else but Greenhead.

J.B. Schofield & Sons Ltd

Greenhead, Linthwaite, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD7 5TST: 01484 842766

E: accounts@jbschofieldandsons.co.uk